Point Austin: Let David Live

The execution of David Powell will not serve justice

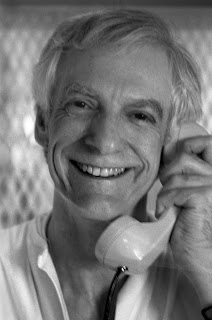

BY MICHAEL KINGHow much pain is enough to make up for irreparable harm? – David Powell

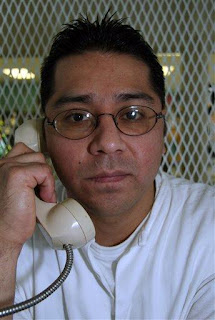

If all goes according to plan, David Lee Powell will be executed by the state of Texas, in our names, on June 15. That’s the date set by state District Judge Mike Lynch at the request of Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg.

This is an execution more than 32 years in the making, and the story exhibits the tortured legal history of many Texas capital cases. The 27-year-old Powell was first convicted of the May 18, 1978, murder of 26-year-old Austin Police Officer Ralph Ablanedo in September 1978. The first conviction was overturned for legal reasons that included prosecutorial misconduct; he was tried and convicted again in 1991, and retried for sentencing only in 1999. Only then was it revealed that Travis County prosecutors (among them then young Assistant D.A. Lehmberg) had concealed potentially exculpatory information from his defense, including their belief that a chief state witness, Powell’s companion Sheila Meinert, had participated in Ablanedo’s murder. Nevertheless, Powell was again sentenced to die and has since exhausted all of his appeals.

Unless Lehmberg should decide to withdraw the execution request or the Board of Pardons and Paroles recommends clemency to Gov. Rick Perry and he concurs – none of which is at all likely – Powell will be executed. Had he been sentenced to life imprisonment in 1978, Powell would have been eligible for parole in 20 years. After 32 years on death row, much of it in solitary confinement, Powell will have effectively endured – in our names – both a life and a death sentence. As Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer has opined, “Where a delay, measured in decades, reflects the State’s own failure to comply with the Constitution’s demands, the claim that time has rendered the execution inhuman is a particularly strong one.”A Changed Man

Powell’s crime was locally sensational, an assault-rifle execution of a police officer during a seemingly routine traffic stop, followed by a brief chase and another shoot-out with Austin Police. Ablanedo left a wife and two children, and the prosecutor’s closing argument was attended by dozens of uniformed police officers wearing mourning ribbons. Even in execution-shy Travis County, Powell’s sentence was virtually inevitable.

Although there was little doubt of Powell’s guilt, there should have been considerable uncertainty about the degree of his culpability. There was the clouded issue of “deliberateness” or premeditation; expert testimony that at the time of the crime he was deeply addicted to methamphetamine and likely suffering from amphetamine psychosis – the chemical equivalent of insanity – was ignored, as was the fact that he had never previously committed violence. The Texas death penalty requires a jury’s conviction of “future dangerousness” – prosecutors summoned psychiatrists nominally to determine Powell’s sanity for trial, then used their testimony to assert Powell’s propensity for violence.

Yet Powell had never been violent before the Ablanedo murder, and by the time of his final sentencing, in 1999, he had spent nearly a dozen years in prison without ever engaging in violence. Testimony in his defense included not only former gubernatorial candidate Sissy Farenthold and attorney general candidate David Van Os (who knew Powell as a young man) but also several prison guards who testified that he was not violent and presented no future threat. We now have 32 years of evidence that, despite that sentence, and now a dozen years of solitary confinement due to prison policy changes, Powell has presented no threat to anyone at all and has served his time as a model prisoner.

Once, there might have been doubt concerning Powell’s “future dangerousness” – now there is none. When we execute Powell next month, we will be executing a different person than the one who, in an irretrievable moment of mad frenzy, committed his terrible crime. If nothing else, Powell’s execution will confirm that the Texas death penalty is not about justice but revenge.Who We’re Killing

Fair-minded people can certainly hold differing beliefs about the death penalty, though in my experience the more people learn about its actual practice, the less likely they are to believe that it serves justice, certainly in any equitable way. The political stakes (especially in a sensational case like Powell’s) are inevitably so high that prosecutors persistently bend the rules to get convictions. The consequent appeals strain and distort the justice system and, more cruelly, the innocent family members on all sides. Restorative justice is essentially impossible, since to avoid a death sentence the accused must not acknowledge guilt or remorse of any kind. Only when his appeals were completely exhausted was Powell able to write an eloquent letter of apology to the Ablanedo family.

“I am infinitely sorry that I killed Ralph Ablanedo,” Powell wrote. “I stole from you and the world the precious and irreplaceable life of a good man.”

Beyond this, Powell has been an exemplary prisoner for 32 years, teaching other inmates, consulting with experts on the Texas criminal justice system, testifying on the rights of prisoners with mental disabilities, and more. He has managed to make something useful and important of his life even in the extreme confinement of death row and the Texas prison system; to kill him now is to surrender to the nihilistic belief that there is no such thing as redemption.

But whether or not you believe that we should execute Powell, you should spend some time reviewing the background and history of his case, available at the website LetDavidLive.org, including an extended video interview with Powell on death row, members of his family, and people who have known him well. The history of the Texas death penalty is a lengthy one of obscure names and dates; it’s a little less abstract when you get to know the person you’re going to kill. It’s undeniable that Powell took a life – “I’m so so sorry for having killed Ralph Ablanedo and stolen from him everything that he might have become,” he says in the interview, “and stolen everything that he was from the people that loved him.” What possible good can come from adding another name, and the inevitably reverberating sorrow, to the long list of the dead?

In December of 2009, David Powell wrote the following letter to the family of Ralph Ablanedo; Ablanedo’s wife, Judy, later married Austin Police Officer Bruce Mills, who also adopted their two children .Powell’s letter to the family of Ralph Abla nedo is posted with this story here.

More information about David Powell’s case and suggestions for potential public action are available at www.letdavidlive.org.